The rapid transition of video and TV to the Internet must be supported by updated policy and regulation

Digitally driven disruption is taking place at a rapid rate and within an unexpectedly wide range of industry verticals, including media and transportation markets. A clear example of this trend is occurring in the media market, where the increasing number of live TV OTT offers is accelerating a transformation of how video and TV content is delivered; as a result, traditional broadcasting needs to become more competitive in response. For instance, a recent report released by the Danish Agency for Culture and Palaces to discuss the impact of new media, argues for immediate action, noting that “in a few years, it may be too late.”1

The current audiovisual regulatory framework is facing a strong challenge from a faster-than-anticipated IP transition

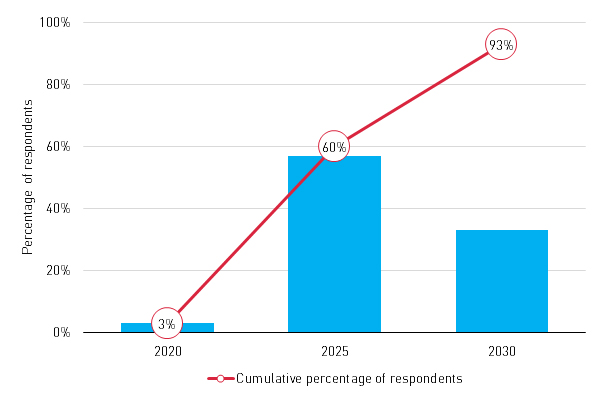

In a survey conducted during the IBC2017 Conference in Amsterdam in September 2017,2 Analysys Mason asked participants to indicate when they thought that the majority of the European Union’s annual TV revenue (equivalent to EUR90 billion) would migrate to online channels. Most audience members reported that this could take place as early as 2025 (see Figure 1) much faster than most experts forecast.3 At this point, video and TV over IP will be mainstream; consequently, policy makers and regulators should be prepared.

Figure 1: Percentage of responses to Analysys Mason’s IBC survey question: “When will IP revenue exceed broadcasting revenue in the European Union?” [Source: Analysys Mason, 2017]

Current TV and video regulation is intrinsically linked with the market structures and the policy objectives that underpin the traditional broadcasting industry. These objectives were designed to ensure that the relative scarcity of channels did not have a negative impact on the market or on content, while at the same time certain obligations were imposed on the broadcasters in exchange for gaining access to a market with high entry barriers. These audiovisual policies and regulations are regularly reviewed by policymakers. However, updates have been evolutionary, and to date, only relatively limited modifications of the current traditional policies and regulations have been implemented – or will be implemented as a result of the latest proposed changes in the relevant laws. As the market for TV and video over IP becomes mainstream, an audiovisual policy and regulatory framework based on traditional services is unlikely to be fit for purpose for the majority of audiovisual consumption.

Other industries such as transport are being digitally disrupted; slow regulatory action may impair broadcasters’ ability to act

TV and video are not the only sectors undergoing digital disruption, nor are they the only ones with a regulatory response. For example, the transport industry has been significantly disrupted by ’uberisation’ (the use of ride-sharing apps to compete in traditional regulated taxi markets), as described in the following two examples.

New York’s yellow cabs

The yellow cabs (which can only operate with a ‘medallion’) that operate in New York have seen their value plummet following the rise of Uber and similar car services. All yellow cabs must have a New York City taxi medallion, of which there are a limit of 13 587, which has driven up prices to over USD1 million per medallion as recently as 2014, when the city auctioned 350 medallions for USD359 million. There are now 63 000 drivers offering services with ride-sharing apps, and the value of traded medallions in the summer of 2017 reached between USD150 000 and USD450 000.4 Taxi drivers report that they are not afraid of competition, but that unlicensed drivers face less restrictions on fares and passenger obligations such as disabled access. These conditions have led to foreclosures for many medallion owners, who find themselves unable to repay loans. As a result, questions are being raised about whether the current rules are appropriate and sustainable.

Uber in London

Transport for London (TfL) has recently stripped Uber of its London operating licence 5,6 (in spite of employing 40 000 drivers and acquiring 3.5 million users after 5 years of service). TfL decided to withdraw Uber’s licence primarily because of concerns about consumer protection and safety. Moreover, Mayor of London Sadiq Khan said that “all companies needed to play by the rules,” endeavouring to create a level playing field where all companies provide similar services and play by the same rules, and that those rules provide certain protective measures for consumers and other drivers.

Lessons for video and TV regulation

Although there are significant differences between the video/TV and transport markets, there may be some analogies to, and lessons that can be implemented, during the evolution of the regulation of video and TV to IP. Most significantly, this evolution must be underpinned by clearly-identified policy objectives that can be implemented in the long term. Once these objectives are clear, a new and future-proof set of regulations must be formulated to deliver these aims (while also protecting competition and consumers) before the ability of broadcasters to meet these objectives is impaired.

What should broadcast regulation look like going forward? Is a transition regime required to protect current players?

Given the faster-than-anticipated migration from traditional broadcasting channels to IP, as well as the potential need to avoid waiting too long and letting the market dictate outcomes that may not be acceptable, two key questions (and associated concerns) should be addressed in the short term.

Would a balanced approach to levelling the playing field provide a long-term solution?

How will long-term policies and regulation shape the future of video and TV markets worldwide in the face of IP migration?

- Should regulation be levelled down long term, or levelled up? Which content policies, economic regulations and obligations will still be required in the future?

- Will there be enough (sustainably produced) domestic content? Will the public needs be met, (for example, for news content and universal content) in the face of an increasingly fragmented market?

- Which content policies, economic regulations and obligations should continue to be imposed on existing broadcasters, and which should be relaxed? Will there be enough diversity and pluralism provided by the market?

- Will it be possible to migrate all TV online or will ‘traditional’ broadcast technology still be required in the future to meet policy objectives?

Is a transition framework required to protect broadcasters from the risks that we have highlighted in our transportation example?

To the extent that existing regulations and obligations on traditional broadcasters are still desirable in the long term, is there a need to consider a transition regime to protect current players in relation to their current obligations and tradable assets?

- Similarly to the transport industry example described above, the traditional broadcasting industry has developed some long-term tradeable assets around, for example. traditional broadcast obligations that could be at risk in the future. New TV over IP-based competition will increasingly put pressure on traditional broadcasting commercial revenue, which in turn is likely to put pressure on the value of regulated broadcasting assets. Regulators might need to consider a transition regime to avoid a similar situation to that of licenced yellow cabs.

In the transport sector, it may have been difficult to predict the popularity of Uber, and thus the incentive by policy makers to ‘wait and see’ was powerful when Uber first was introduced. However, the success of video and TV over IP is now not hard to predict. Policy makers should begin to outline which policy objectives are most important to maintain in order to ensure a smooth transition to a digitally dominated video and TV ecosystem in the not-too-distant future and start acting accordingly now.

Analysys Mason has broad experience in the audiovisual, telecoms and digital sectors. We work with regulators and policy makers and players in audiovisual and telecoms regulatory, policy and competition issues, all of which are increasingly considered in relation to digital distribution (obligations, access, prominence, territoriality, copyright and piracy). For further details, please contact Michael Kende.

1 Globalisation of the Danish Media Industry. Studies of international players’ impact on the Danish media market, Danish media providers and Danish media content. Danish Ministry, June 2017

2 For further details, see Lluís Borrell’s presentation from the IBC2017 Conference: Platform Futures Stream: Is IP really having an impact on broadcasting.

3 For further details about the survey, see Lluís Borrell’s LinkedIn posting: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:6315509768555368449.

4 New York Times (New York, NY, 10 September 2017), Taxi Medallions, Once a Safe Investment, Now Drag Owners Into Debt. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/10/nyregion/new-york-taxi-medallions-uber.html.

5 Transport for London (London, 22 September 2017), Licensing decision on Uber London Limited. Available at: https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/media/press-releases/2017/september/licensing-decision-on-uber-london-limited.

6 Guardian (London, 23 September 2017), Uber stripped of London licence due to lack of corporate responsibility. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/sep/22/uber-licence-transport-for-london-tfl.

Downloads

Article (PDF)Authors

Michael Kende

Senior AdviserLatest Publications

Article

Policy makers must explore all possible levers to achieve gigabit connectivity ambitions

Report

AI for connectivity: how policy makers can help digitalisation

Report

LEO satellite broadband: a cost-effective option for rural areas of Europe