How Internet exchange points (IXPs) drive growth of the Internet ecosystem in the Middle East: the case of UAE-IX

Analysys Mason previously wrote about how Internet exchange points (IXPs) in African countries such as Kenya and Nigeria are contributing to the growth of the surrounding Internet ecosystem in several ways. This article examines whether IXPs are (or would be) similarly beneficial for the growth of the Internet and the digital economy in the Middle East. According to TeleGeography's IXP map there are over 25 exchanges in Africa, compared with 7 in the Middle East. In the Middle East, UAE-IX provides a good case study on the impact that an IXP can have on a region, having recently celebrated its second anniversary and most likely being the largest IXP in the region.

UAE-IX is an initiative by datamena, a brand of UAE operator du, to create a regional carrier-neutral IXP, with the support of two reputable international partners: global data-centre provider Equinix is in charge of operating the data centre where the IXP is hosted, while the DE-CIX team from Germany is in charge of operating the IXP.

A range of other players have been involved in the UAE-IX initiative – including flagship content creators/distributors (for example, Google and video-game creator Valve), Internet service providers (such as Emirati du, Kuwaiti Zajil and Vodafone Qatar), content delivery network (CDN) operators (like Akamai and Medianova) and international carriers (e.g. Cable & Wireless, BICS) – as they believed in the benefits that could be achieved if the industry co-operated to make use of this IXP. As a result, UAE-IX has been able to reach a critical mass, with more than 30 different parties now connected at the IXP. To illustrate the benefits available to players that use UAE-IX, Selevision (a provider of multimedia content to consumers and carriers) is using UAE-IX to peer with regional operators, thus leveraging its presence at the IXP to give its consumers (or "eyeballs") an excellent user experience.

The emergence of a carrier-neutral IXP in the Middle East has also stimulated regional discussions about traffic exchanges, which did not really happen before: prior to UAE-IX, operators and content players peered outside the region (e.g. in Europe) and did not consider the option of doing this locally. This is now changing, however, with lively discussions underway between stakeholders about local peering. For example, when operators met to discuss peering arrangements at the Middle East Network Operator Group (MENOG) meeting in April 2015, this was well attended by a wide range of participants – including over 60 representatives from regional operators (UAE, Bahrain, KSA, Kuwait), global and Tier-1 carriers, content owners, CDN, local broadcasters and financial services companies.

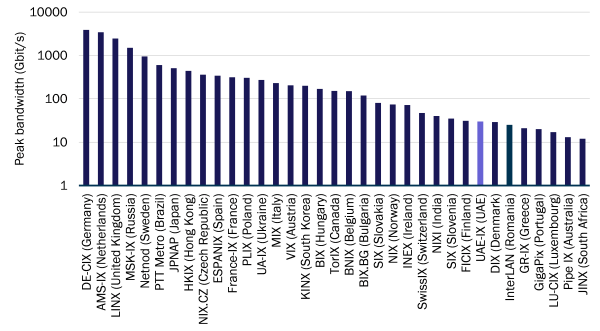

As a result, as of February 2015, UAE-IX supported a peak bandwidth of 30Gbit/s, which is comparable with that of many older European IXPs and higher than the combined bandwidth of the two largest IXPs in Africa (JINX in South Africa and TunIXP in Tunisia). According to public data, UAE-IX is already ahead of the Greek, Portuguese and Romanian IXPs, which highlights its regional remit.

Figure 1: Ranking by size of some of the largest IXPs (excluding those in North America) [Source: Public sources, February 2015]

Note: This chart excludes IXPs from the USA, and only shows those exchanges which publish traffic data on their website.

This success story is stimulating ambitions for other countries to set up their own IXP: several other Middle Eastern countries are currently thinking about starting or expanding their IXPs, driven by initiatives from their government or regulator. For instance, TRA in Oman recently issued a consultation on the merits of having an IXP in the Sultanate and on the regulatory intervention needed to facilitate such a launch. Similarly, NTRA in Egypt is reported to be eager to develop its existing IXP further. In these cases, we believe it is important to conduct a proper impact assessment on the IXP, as the range of benefits achieved can vary depending on the geographical scope of the IXP and its ability to attract local incumbents to connect to it. Not all IXPs can successfully achieve regional ambitions, just as not all airports/airlines can exert regional influence. However, as is the case with airports/airlines (e.g. Abu Dhabi, Doha and Dubai), there may be room for more than one regional IXP to cover the Middle East, if the right ecosystem is in place. By joining IXPs, incumbents may accrue benefits in the medium and long term, as they will also benefit from traffic growth in local markets which will require more bandwidth or more connectivity locally.

In conclusion, the example of UAE-IX shows that there are clear benefits of setting up IXPs for the purpose of having more content generated and hosted locally, both in the Middle East and more generally. However, a number of aspects need to be looked into when setting up such an IXP, such as:

- defining appropriate geographical ambitions

- ensuring there is a suitable industrial and regulatory environment, and

- bringing together a team of stakeholders to make the IXP a success.

There are opportunities and challenges that must be overcome in relation to the definition and implementation of an IXP strategy. Analysys Mason can assist operators, policy-makers and other stakeholders to conduct IXP impact assessments, to define a strategic vision for the development of an IXP, and to create a successful plan for its implementation.

Authors